-

What is Ultra HDI?

With Ultra HDI, small features come with big decisions. READ MORE...

-

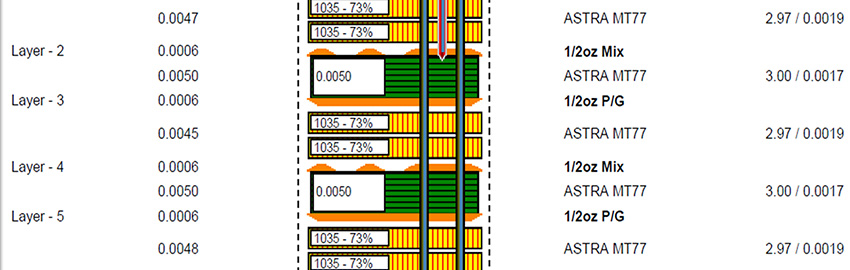

The Critical Nature of PCB Stackup

The stackup supports every layer above it. READ MORE...

-

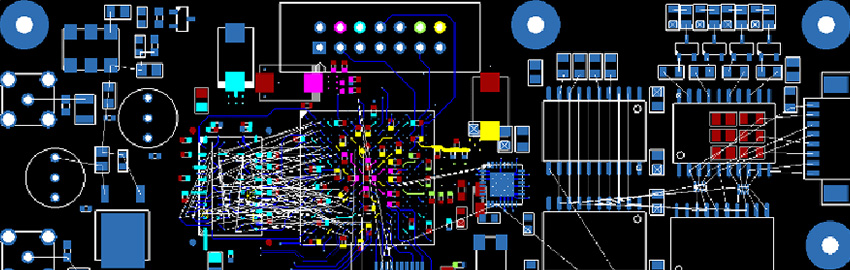

The PCB Design Review Process

A structured design review process ensures alignment. READ MORE...

-

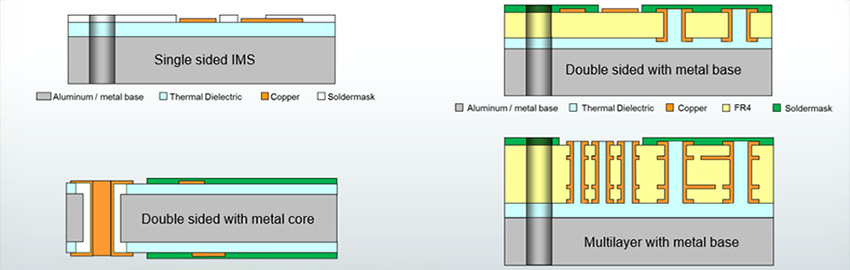

Metal-Core PCBs and Thermal Management

Catch heat at the board. READ MORE...

Homepage Slideshow

What is Ultra HDI?

With Ultra HDI, small features come with big decisions.

The Critical Nature of PCB Stackup

The stackup supports every layer above it.

The PCB Design Review Process

A structured design review process ensures alignment.

Metal-Core PCBs and Thermal Management

Catch heat at the board.

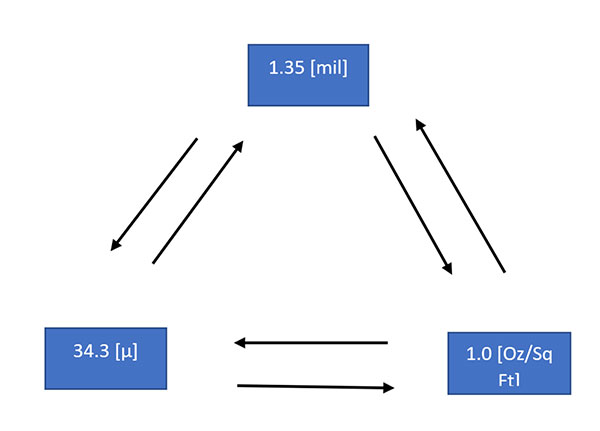

Smooth copper isn't always what it is purported to be.

Smooth copper isn't always what it is purported to be.

Catch heat at the board before it turns into a full-time job.

Catch heat at the board before it turns into a full-time job.