Time-to-market advantages encourage getting designs to scale quickly.

Time-to-market advantages encourage getting designs to scale quickly.

Time to market is one of the most significant factors in the success of a product. The advantage of being first to enter space is that all who come after must be clearly better in some way. Whether it is a feature that resonates with buyers or a lower price, it will be an uphill battle for later entrants to gain market share. Recognition and higher gross margins go to the first mover. Even then, innovations can quickly become commodities.

This is never truer than during a period of upheaval. I was around for the digitization of the phone system. We went from Alexander Graham Bell’s invention of the telephone to using those same wires to carry data. As you know, that caught on well.

Back in 1984, the US government broke up the telephone monopoly, which gave rise to seven regional providers (the so-called Baby Bells) and one think tank (Bell Labs). All of a sudden, the race was on to provide equipment that could multiply the number of conversations held on a single T1 line.

Figure 1. Can you imagine going on vacation and leaving your phone behind? This was our world in 1985. One of the innovations of the time was lower-priced long-distance calls after 7 pm. Local calls were part of the baseline service, but one county away could be on a minute-by-minute rate.

Backfilling with experts. I found a job building telecom racks for a small company named Grainger Associates. The old-school analog equipment could host 24 channels. Through the magic of multiplexing, we increased the throughput from 24 up to 60 channels, then 120, 384 and finally 476 channels on a single T1 line. One 7ˈ (2.1m) rack would sell for the price of a midsize Mercedes.

That was just for the rack with backpanels. Filling it with die groups (eight boards plus a power supply, times 12) would fetch the same money as an average Bay Area house – say, $200,000 in mid-eighties currency. We also had 11ˈ (3.3m) racks for the Baby Bells, which were contractually prohibited from purchasing the 7ˈ versions.

Our team’s core competency was modulators, demodulators and the quirky T1 interface. The sleek analog-to-digital and digital-to-analog boards were sourced from another company. The power supply was also a “buy” product rather than a “make.” The remaining two boards were designed in collaboration with a service bureau. Our schematics for those were turned into boards on-site under the supervision of our engineering team.

Each generation required an entirely new die group. We also had a line of echo cancellers and the company’s original product, a point-to-multipoint radio system used by offshore oil wells. A telecom revolution spawned the internet via dial-up service. A wireless revolution followed, giving us cellphones and later, the all-encompassing smartphones. My involvement was at a company called Spectrian. We were a vendor for Qualcomm, and then Samsung, when QCOM sold its cellular base station segment.

When a new company went public in the same space, the market reacted. Our CEO came right out and told us, “We would make a good short.” I wish I knew then what he meant. Our stock cratered, and we were eventually acquired by a larger telecom outfit.

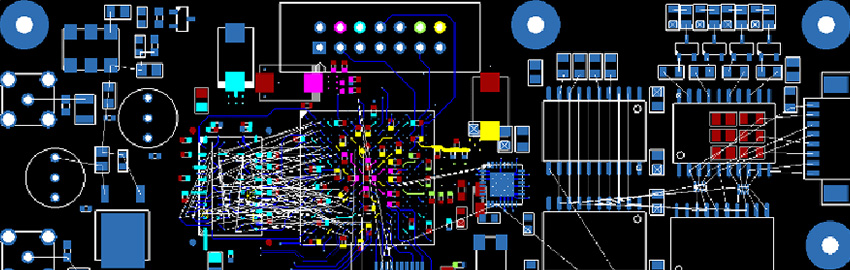

Figure 2. Two versions of a double-sided, mixed-signal PCB. It was used as a correction board for a multi-carrier linear amplifier for a 3G cellular base station. The HASL board came first (circa 1996), showing the DSP circuit, followed by ENIG in 1997 with the analog side up. The first one was a team effort, while the final iteration was a minor improvement, including a finish more conducive to surface mount technology.

When it came to smartphones, anyone in the camera business felt the seismic shift. So did the people who made maps, pagers, flashlights, watches, compasses, Rolodexes, calendars and so on. Just look at all the apps on your phone to know that we’re only scratching the surface. Don’t think for a minute that phone makers have decided to stop disrupting the electronics landscape.

Today's companies face yet another revolution. Artificial intelligence incorporates machine learning, large language models and other branches of advanced software engineering. There could be 1,000+ opportunities out there with myriad enterprises seeking the golden ring. The stakes couldn’t be higher. First across the finish line wins.

A contractor’s tale. My second PCB designer job was as a contractor for six months. I designed edge routers for enterprise customers. Those two boards were some of the toughest because I had been doing analog boards the previous nine years. I wasn’t really qualified, but I knew the hiring manager from Granger Associates. I also had four more interviews scheduled, including Nvidia (!), and used that leverage to force him to hire me on the spot. Y2K was a good time to be a board designer.

With about two months left on that six-month contract, I established a one-man service bureau with a single client. My hours were from 4 pm to 8 pm, five days a week, until the other contract ended. Then it became my day job, though the company grew no further.

The manager was from the nine-year stint, so, of course, it was more analog. Lance was both manager and mentor, and even called me into a third job, again pulling me away from a digitally focused position. (I guess I was born to be analog!) Around that time, I was told that board designers were like Bay Area houses.

It’s “who you know,” as they say, but also them knowing what you know.

So, that’s my background as a consultant. It was based on expertise in a particular field. Over that time, I used three brands of ECAD tools: EE Designer, Pads and Allegro, the latter being my only tool from 1996 to present. Being an expert on a tool and a technology are the specialized skills that open doors.

Networking works, but there are pitfalls to avoid. Another mentor, this one from Google, also hired me into two subsequent companies: one designing PCBs for lidar sensors, the other as a contractor designing laser-based communication satellites for the US government. It’s who you know, but also them knowing what you know. Finding a service bureau with experience in your field is a safer bet than a random selection.

In all cases, I still had to pass an interview. SA Photonics rejected me outright when the agency sent them my résumé. None of my products was in orbit. They wanted someone who already had the “right stuff.” Eight years of laser technology weren’t enough. It was only the insistence of Matt, my previous mentor/manager and its new VP of engineering, that I got the job.

Any temp, vendor or contractor should be scrutinized before they warm the chair of a CAD station on your behalf. It is your prerogative to interview potential candidates. They tend to charge a lot, where the person doing the actual work sees maybe two-thirds of the total, to keep the agency, bureau or consultancy afloat.

Also, look for a service bureau with a global footprint. It can work around the clock and rates can be lower. It can send someone to your office during the day while a second shift offshore pulls in the schedule.

Business uses money to keep score. When a product is released to the market, it comes with considerable baggage. Just like the PCB fabricator charges a nonrecurring engineering fee on top of the piece rate, the final product has a development cost to cover before recognizing a profit.

The cost of goods sold (BoM cost and labor over a period of time) plus overhead such as advertising, distribution and maintaining the entire facility, including labs, parking lots, and everyone’s salary, must be paid out of profits from the selling price. Additional engineering to fix a problem will add to the number of units that must be sold to break even. Warranty costs and product returns erode profit margins.

Competition, advancements in technology, geopolitics and customer perception are just some of the things that affect results in the factory. Success can be fleeting as more companies enter the market. Rest on your laurels at your own peril. Improvement and innovation must be nonstop as a matter of survival.

Coming full circle, the company that creates a new product segment is the one that will be able to charge the kind of prices that will quickly pay off development costs. A good service bureau will help win that race to market, but only if it is well-managed on our end. Whether it’s enterprise hardware or consumer electronics, every product becomes a commodity once enough vendors enter space. Strive to be first, my friends.

John Burkhert, Jr. is a principle PCB designer in retirement. For the past several years, he has been sharing what he has learned for the sake of helping fresh and ambitious PCB designers. The knowledge is passed along through stories and lessons learned from three decades of design, including the most basic one-layer board up to the high-reliability rigid-flex HDI designs for aerospace and military applications. His well-earned free time is spent on a bike, or with a mic doing a karaoke jam.

Time-to-market advantages encourage getting designs to scale quickly.

Time-to-market advantages encourage getting designs to scale quickly.