Successful flex and rigid-flex assembly depends on controlling moisture.

Successful flex and rigid-flex assembly depends on controlling moisture.

Questions about baking and assembly come up at least monthly, if not more often. Several factors can impact successful assembly with flex and rigid-flex.

Environment. As a rule, delamination is usually due to retained moisture. The rapid rise in temperature during reflow causes moisture to change from liquid to expanding vapor or steam. This expansion can result in delamination.

Storage and factory conditions can certainly impact assembly success. Baking times and temperatures are definitely humidity-dependent. Most guidelines are not defined based on a specific condition. I would treat them as a baseline, and if humidity is high or if parts were exposed to a long liquid cleaning, I would increase bake times.

Some assemblers use vacuum ovens for drying. The advantage is that this can be done at lower temperatures because the boiling point of water drops as the vacuum is applied. The vacuum also provides mechanical encouragement to draw the moisture out. It’s just another technique that can be employed.

It is important to process immediately after baking. If you can’t process these circuits right away, store them in a desiccant chamber to keep them dry. A desiccant chamber cannot dry parts, but it can keep them dry for long periods.

Soldering thermal profile. Regardless of the PCB design, the assembly solder type will drive your solder profile – lead-free solders will mean higher temperatures. Often, there is a tendency to jump to a 260°C profile. However, before going there, consider lower temperatures. Many lead-free solders will reflow at lower temperatures. Data tell us that as the reflow temperature rises, the increase in the amount of stress on all the materials and plated through-holes is not linear. These stresses rise much faster than the temperature increase. Often temperatures of 245°C or even as low as 235°C can be successfully employed. This can result in a dramatic reduction of stress on the board and assembly. As a result, the odds of delamination will be reduced.

Material selection. Certainly, every material has a different moisture absorption rate as well as a rate of drying. Some materials absorb moisture slowly. However, they also release it slowly, so it is still important to bake these materials if they have been exposed to moisture for a long time. In some cases, you may need to extend bakes to account for hygroscopic materials or long exposures.

For rigid materials, epoxy-based laminates do not absorb moisture as much as polyimides. Fluorocarbon materials do not really absorb moisture as they lack polar groups, which are receptors to moisture. Liquid crystal polymers (LCP) are also known for low moisture absorption.

Flex materials, specifically acrylic adhesive and polyimide film, are known to absorb moisture. Flex materials can absorb ambient moisture within 30 min. Making sure these are dry during reflow is very important.

Generally, moisture absorption is an issue only during reflow processes, due to high temperatures and rapid temperature rises. For most PCBs, the most stressful condition they will ever see is solder reflow. In most applications, they are unlikely to see anything close to this in actual operation.

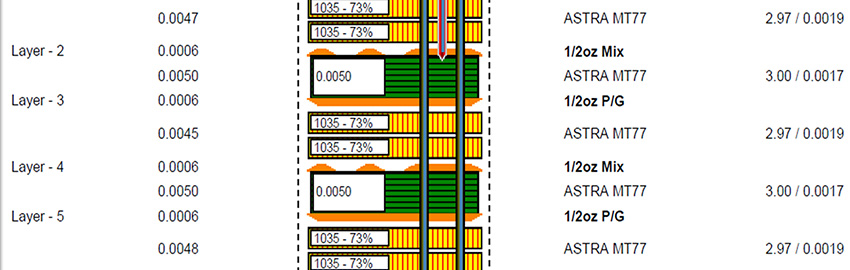

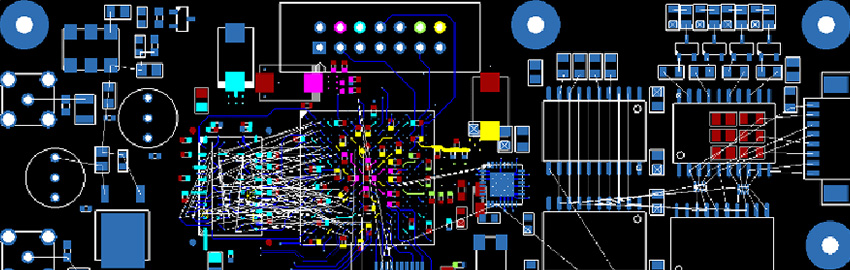

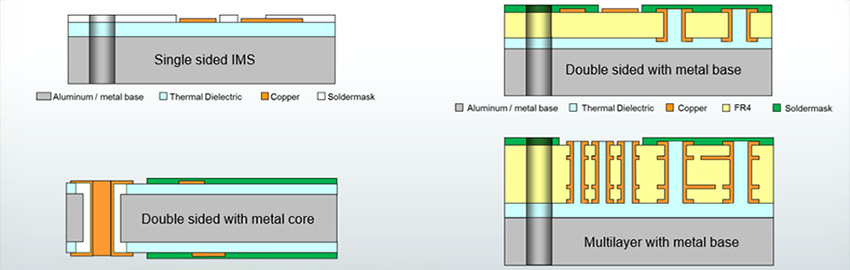

Stackup. Additionally, the overall PCB construction and artwork pattern are variables to consider. Thermal mass and heat absorption rate come into play. Polyimide film is very sensitive to infrared energy and will absorb IR energy very rapidly. It is important to avoid placing IR systems on flex circuits.

One- and two-layer flexes are very low in mass and will reach reflow temperatures quickly. In addition, it is easy to bake out moisture. Both baking and reflow profiles can be managed accordingly. Baking can be successful in just a couple hours.

As we add layers, thermal mass increases. A part with many layers or very thick has a lot of mass to dry, and it can take a long time for moisture to exit. Bake times need to increase to ensure the parts are dry. Bake times may increase to 6-12 hr.

Rigid-flex PCBs bring other complications. The number of flexible vs. rigid layers will impact moisture capacity. In the rigid sections, the flex is sandwiched inside the rigid material. If there is moisture retained in the flex layers of the rigid, it can be trapped and difficult to remove.

The rigid sections are also much thicker than flex regions. As a result, flex regions get up to reflow temperature and stay there much longer than rigid sections. This puts more stress on the flex region. Some assemblers will apply “shields” over flex regions to reduce heat absorption. This can be as simple as a rigid laminate.

From the artwork perspective, plane layers will impact moisture absorption and expulsion. It may be harder to get the moisture in because the plane blocks it. Conversely, it also traps it since the moisture can’t exit through the plane. It needs to exit horizontally from the side of the part. It can take much longer to remove moisture under planes. Essentially, think of this as a plumbing challenge. What is the path out, and how do you encourage it?

So, in summary, accommodate your design by using prebake times sufficient to drive out as much moisture as possible. An extra few hours of oven time is a small price to pay. Once dry, keep ’em dry until soldering. Finally, keep your cool – if a lower reflow temperature is used, delamination is a rare occurrence.

Nick Koop is director of flex technology at TTM Technologies (ttm.com), vice chairman of the IPC Flexible Circuits Committee and co-chair of the IPC-6013 Qualification and Performance Specification for Flexible Printed Boards Subcommittee; This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.. He and co-“Flexpert” Mark Finstad (This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.) welcome your suggestions.

Successful flex and rigid-flex assembly depends on controlling moisture.

Successful flex and rigid-flex assembly depends on controlling moisture.