Clarify key features, but don’t use 10 notes where one will do.

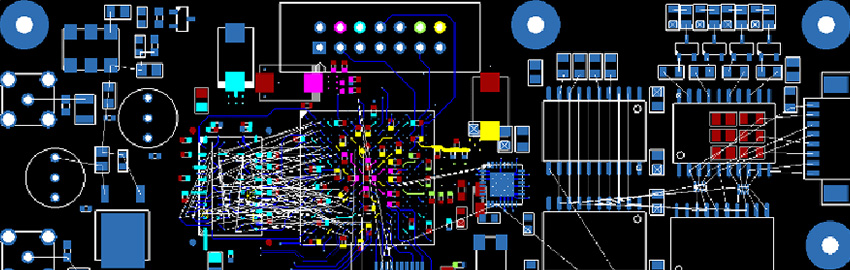

You have been tasked with documenting a flexible circuit you are preparing to send out for quotes. Should specific drawing notes be included?

I recently received a drawing from a prospective customer for a simple two-layer flex circuit. The first page of the drawing had their drawing notes … all 42 of them. While every good drawing should include notes to clarify important features, you don’t want to over-specify either. As I worked my way through the notes on this particular drawing, I quickly realized a large majority were restatements of requirements already in IPC-6013, and could have been covered with the note, “Circuits shall conform to the requirements of the latest revision of IPC-6013, type X, class X, use X (replace “X” with the type, class, and use of the circuit being specified). That single note would have eliminated more than half the notes on this drawing!

Your best bet when generating drawing notes is to begin with the IPC-6013 note referenced above. Beyond that, focus notes to attributes specific to the design, and limit them to features critical to the performance and/or reliability of the circuit. Next, I will go through some of the most common features to cover in your notes.

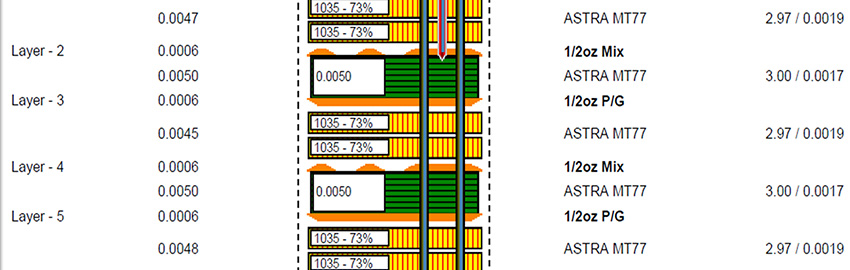

Materials (should include stackup). Flexible circuit base materials options are plentiful: different manufacturers, different thicknesses, etc. Ensure the drawing clearly specifies any materials critical to the function of the circuit. At the same time, over-specifying can unnecessarily increase the cost of the circuit without providing any benefit in performance.

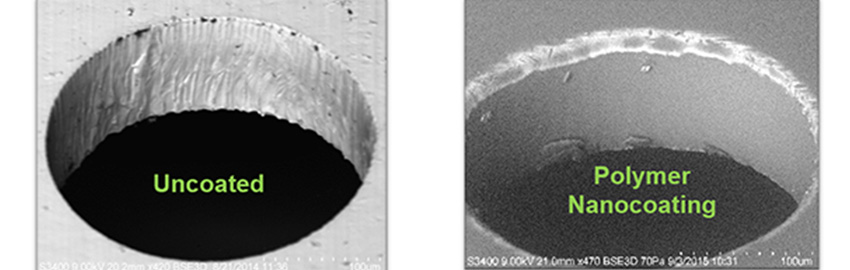

For instance, virtually all materials used in a flexible circuit are documented in one of the IPC material specifications (i.e., IPC-4202, IPC-4203, IPC-4204). All critical features of each material are covered in the associated slash sheets in these specifications, which can be referenced in the drawing notes block. All manufacturers of these materials must ensure their products conform to these specifications. For this reason, I typically recommend that the drawing does not specify a particular manufacturer.

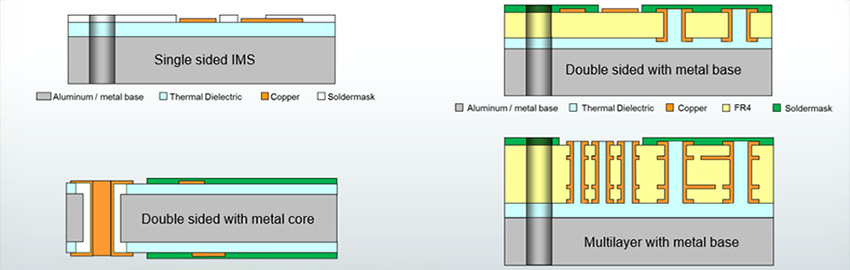

The same is true of material thicknesses. The drawing should include a cross-sectional view that depicts each unique construction area of the circuit. All material thicknesses critical to the performance of the circuit should be clearly labeled in the cross-sectional view. If the individual material thicknesses for specific performance attributes (like impedance) are required, they should be specified. If no critical material thicknesses are required, specify only overall finished thickness in each unique construction area. By doing this, the supplier has the option to pick the materials that best meet the final thickness requirements and will also work best with its processing methods.

Final finish. While IPC-6013 specifies solder as the default final finish if nothing is indicated on the drawing, far and away the most common final finish currently used is ENIG (electroless nickel immersion gold). If a final finish is not specified in the notes, most fabricators will want to use ENIG. This is fine if the circuit has only ZIF contacts or SMT components. But if the application requires a solder finish or wire bonding, specify that requirement in the notes. Soft gold over nickel or ENEPIG (electroless nickel electroless palladium immersion gold) are the most common finishes for wire bonding. Solder finish is becoming so uncommon, many flexible circuit suppliers do not even support HASL equipment. For this reason, if a solder final finish is needed, specify only something like “solder finish,” rather than “HASL solder finish.” That will give the fabricator the option to add the solder in a way that works best for them (e.g., solder plate and reflow, etc.). Also, if the design requires RoHS compliancy, reference it in your final finish drawing note.

Miscellaneous requirements. Any other requirements critical to the performance or reliability of the flex circuit should also be covered in the drawing notes. These include, but are not limited to:

- Static or dynamic application (unless you already use “A” or “B” in previous note)

- Operating temperature range (use C?)

- Bend areas

- Bend radius

- Bend angle

- Environmental exposure.

Including notes on the above items will permit the fabricator to evaluate if the flex as designed will be suitable for the specific application. For example, if I get a drawing that states “Use B and Use C,” I would have concerns and relay them to the customer. “Use B and C” would indicate a dynamic application in a high-temperature environment. Typically, those two requirements don’t play well together.

If multiple signatures on the drawing are required prior to formal release, it is not a bad idea to let the fabricator review it prior to the signature rounds. This way, the fabricator can do a quick “once over” and flag any omissions. •

Mark Finstad is director of engineering at Flexible Circuit Technologies (flexiblecircuit.com); This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.. He and co-“Flexpert” Nick Koop (This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.) welcome your suggestions.